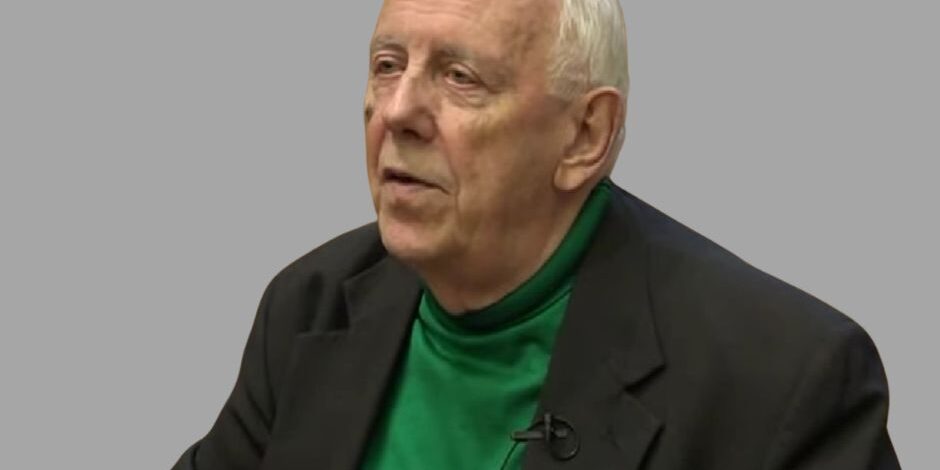

Many of the tributes published recently for the Scottish-American social and moral philosopher Alasdair Chalmers MacIntyre, who died in the United States on May 21 at the age of 96, are tinged with personal experiences and memories. That many of these originate from warring worlds of thought reflects the genuine perplexity many experience when attempting to pin MacIntyre onto an academic map.

MacIntyre has been described in many ways: a “revolutionary Aristotelian,” a “Marxist-Catholic-Thomist,” a “communitarian virtue ethicist,” and “an atypical conservative” traditionalist.

Robert P. George, who is Professor of Jurisprudence at Princeton University, writes on X: “a striking thing about Professor MacIntyre was that he was impossible to classify ideologically. Was he a progressive? Not really. Was he a conservative? No. A centrist? Not that either. He was ‘sui generis.’

I remember, during a moral philosophy class, being assigned one chapter from MacIntyre’s best known work After Virtue, first published in 1981 and never out-of-print since.

As I read in a stuffy corner of a suburban library, I was jolted out of whatever drowsiness I was drifting into. The opening chapter is a startling, dystopian portrait of a shattered moral world, as memorable as Josef Ratzinger’s opening chapter in Introduction to Christianity.

After Virtue is a demanding read, but at the same time is alive with a fluent and robust critique of the loss of a shared narrative and tradition in Western society, the drabness of abstracted analytical studies, inhumane Marxist determinisms as well as offering a hefty regret for the futile “emotivism” of liberal thought. He pricks the inflated and heroic passions of Nietzsche’s “amoralist” man, seeing him as a petty narcissist “who transcends, finds his good nowhere in the social world to date, but only that in himself which dictates his own new law and his own new table of the virtues.”

Lights went on—and I read to the end. For good measure I also resolved to read Jane Austen not only for her brilliant story telling but also for her attention to character, virtue and life-purpose.

John Cuddeback, Professor of Philosophy at Christendom College recalls, “Back in the ’90s, for us graduate students, aspiring intellectuals and young professors, MacIntyre was an utterly unique inspiration: Here is someone deeply conversant in contemporary philosophy who has recognized in the Aristotelian/Thomistic tradition a treasury of wisdom.”

MacIntyre’s expansive and often contrarian wit, personality and critical vision fired the long journey of his life, through three marriages, four children and what he called his “nomadic” intellectual and spiritual path in life as well as his physical journey from Scotland, England and then the United States and many notable university posts.

He was born in Glasgow, and completed university degrees (though never a doctorate). During the post-war gloom of England he abandoned Anglicanism and became an atheist political activist and leader in a number of Trotskyist and Marxist organisations including the International Socialists. For a time he edited the International Socialist Journal.

MacIntyre left the United Kingdom and, in his attempt to articulate a coherent account of the common good, telos and purpose for human action in practice, was drawn to the tradition of Aristotle and then to St Thomas Aquinas. He converted to Catholicism in 1989 and increasingly acknowledged the role of grace in the moral life.

It is a tribute to MacIntyre’s important contributions to modern philosophy that Alex Callinicos writes in the Socialist Worker of the lasting value of MacIntyre’s social and cultural critique forged in his Marxist days. This expansive and critical vision led him to abandon Marxism but also to decry the intellectual poverty of Enlightenment-bred thought.

Although mystified by MacIntyre’s embrace of Catholicism and Thomism, Callinicos concedes that “MacIntyre develops his argument with terrific intelligence, erudition and panache.”

Stanley Hauerwas, the Anabaptist theologian strongly influenced by MacIntyre, argues in an interesting interview that MacIntyre warned against a simply reactionary response to the pandemic of atomism and loneliness evident in the contemporary world. He says: “Alasdair MacIntyre, for one, resists being called a communitarian—he fears that in this place and time such calls are bound to lead to nationalistic movements. Those who hunger for community should never forget Nuremberg.”

Professor Tracey Rowland, the renowned Australian theologian and St John Paul II Chair of Theology at the University of Notre Dame Australia, acknowledges the importance in her own work of what she calls MacIntyre’s “tradition-constituted rationality.”

She told the Thomas More Centre this week that her doctorate was a synthesis of MacIntyre’s historically alert “philosophy of culture with Ratzinger’s theology of culture.”

Professor Rowland explained: “My Thomism is MacIntyrean but unlike a lot of Thomists he understood the importance of history and culture, but he was not a cultural relativist. Like St Edith Stein (on whom MacIntyre wrote) he kept reading and thinking until he found an intellectually coherent explanation – and that was Thomist Catholicism.”

As both cultures of the left and the right descended into technocratic or politicised departments of management, Professor Rowland says, “What I learned from MacIntyre is that bureaucracies are hostile to all forms of excellence!”

“MacIntyre left Marxism once he understood that its only achievement was the creation of bureaucracies that oppress people and create a whole new class of oppressors.”

We asked the philosopher Professor Hayden Ramsay who is currently the President of the Catholic Institute of Sydney (and, like Professor Rowland also a gracious patron of the TMC), for some brief thoughts about the recent death of MacIntyre.

He recalled: “I went to Alastair MacIntyre’s Gifford Lectures in Edinburgh in 1988—the lectures that were published as Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry. These lectures were like thought being created before your eyes, not simply a reordering of others’ views but new and independent insight.”

Professor Ramsay, a knowledgeable devotee of opera, makes a memorable comparison: “Although analytically skilled, his style wasn’t to dwell on details with laser-like attention but to offer masterly, creative oversight—not a Birgit Nilsson of a mind, more a Maria Callas.”

He also notes that even more than being a “revolutionary Aristotelean,” MacIntyre proved himself a highly innovative Thomist observing, “I was thrilled by his veneration of the mind of Fr Herbert McCabe.”

Professor Ramsay, a leading Australian Catholic philosopher/educationalist who also has his roots in the incisive Scottish philosophical tradition (though from the Kingdom of Fife rather than Glasgow) said, “MacIntyre’s was one of the finest minds to emerge from Scotland since the Enlightenment.”

Anna Krohn

Executive Director

Thomas More Centre